Educating Mary and Susie: Paradise 1901-1902

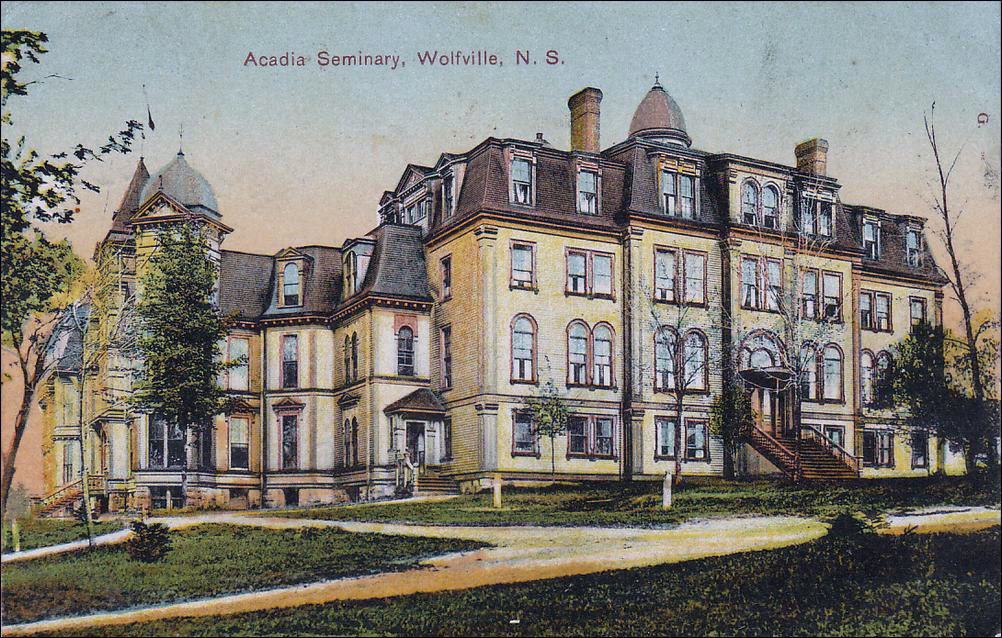

Among the students who returned to classes in January, 1902 as mentioned in Bridgetown’s Weekly Monitor newspaper, there were two young women returning to classes at the Acadia Ladies’ Seminary in Wolfville. Their education at that Seminary was the thin edge of a mighty wedge, whether they knew it or not.

Mary Amelia Delap and Susie Amelia Leonard are in this group photo.

Queen Victoria died on January 22, 1901, but the Victorian world of “separate spheres” for men and women remained. The sphere for women was private/domestic- her household and her children were her concern. The sphere for men was public\business\political.

Obviously, the Victorians believed, the educational needs of these separate spheres were also separate. Women could “get out of the house” to visit female friends and shop, and to do considerable volunteer work in benevolent organizations, even including those that advocated for political or legislative causes to protect family and community. But there were so many constraints.

Politically: “Technically, until 1851 women could vote because the only voting requirement was land ownership. There is documentary evidence from 1793 and 1806 that a handful of women did vote in elections held in those years. In 1851, legislation was enacted to explicitly exclude women from voting. The property requirement was also eliminated. In 1918, women were explicitly included in the legislation, but could only vote if they also fulfilled the property ownership requirement. Finally, in 1920 women in Nova Scotia achieved universal suffrage.” ¹

Economically: Women did run businesses of a private or limited nature, such as inns, boarding houses, private schools, and local stores, all of which some Paradise women did even in the early 19th century in Paradise, especially if they were widows or spinsters.

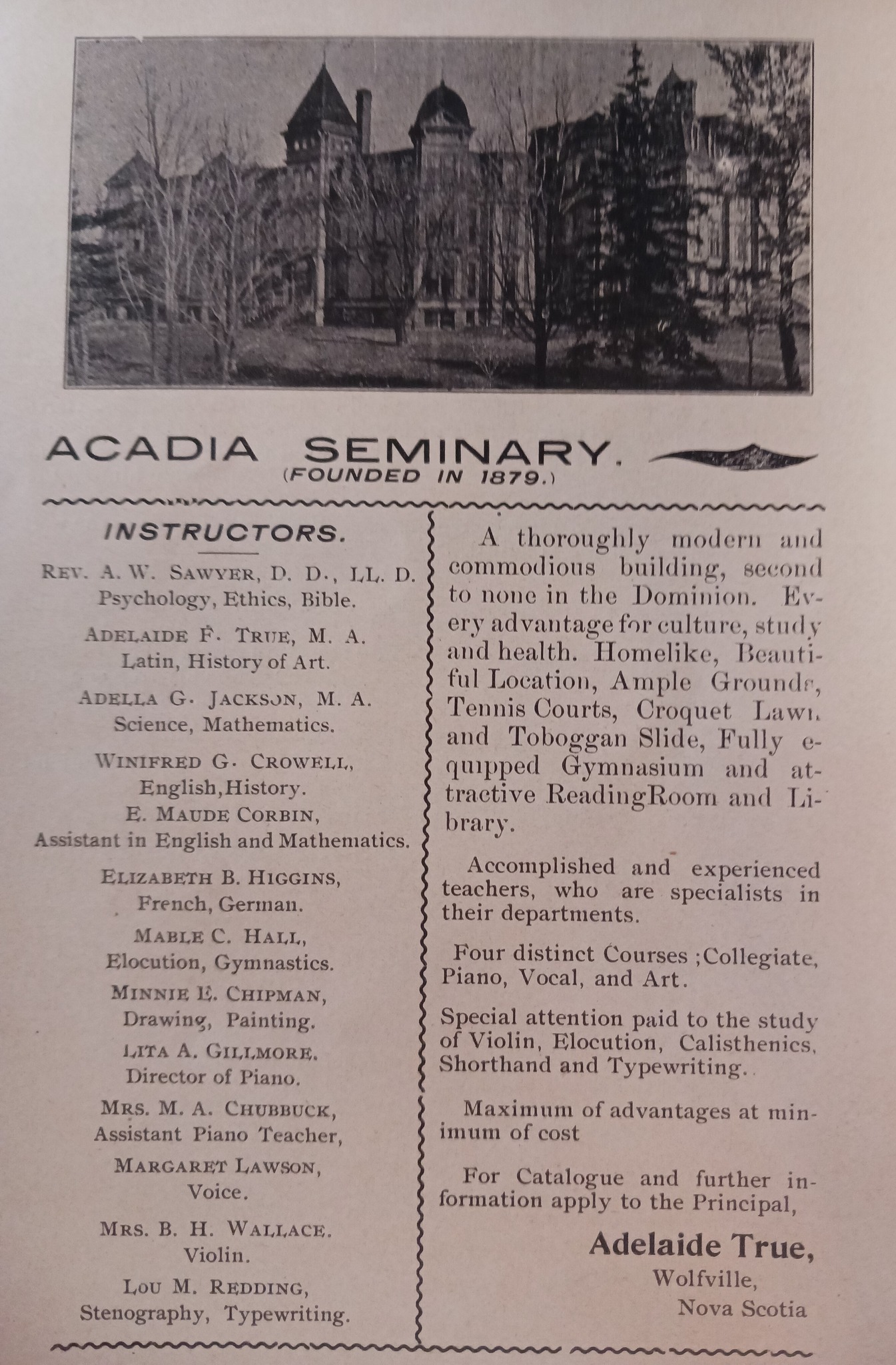

Educationally: It came down to “The ladies, God bless them! The women, God help us!” It was OK to have a “Ladies’ Seminary “on the Acadia College campus, a kind of finishing school for young women to prepare them to improve and enhance their marriages and communities. Women from families who could afford the fee would be advantaged.

Acadia Ladies’ Seminary in 1907

We talk today about a “glass ceiling” but for women of Mary and Susie’s era, there was a whole glass orb! If they wanted to go outside their sphere, they could be pushed back by opposition, dismissal, or ridicule.

A famous example: The influential Presbyterian minister in Nova Scotia’s mid-19th century, Reverend Robert Sedgwick, actually advocated for the addition of biology, geology, entymology, and ethnology to women’s curricula, but there was a hitch- it was only to ensure that she would not betray “her entire ignorance and the defective nature of her education” and reflect badly on her husband.

Sedgwick warned at the end of his address to the Halifax YMCA in 1856 that “. . .there are other ‘ologies as well of which no woman, if she is to move in her sphere as she ought to, can afford to remain ignorant. There is the sublime science of washology and its sister bakeology. There is darnology and scrubology. There is mendology and cookology in its wide comprehensiveness… Now, all this knowledge must be embraced in any system of female education that pretends to prepare women for the duties of life.” ²

Mary Amelia Delap and Susie Amelia Leonard grew up in this ethos; we have no knowledge of how they felt about it, though we know they seem to have done well enough within it. And the Acadia Ladies’ Seminary was a natural step for each of them, for a number of reasons.

For one thing, the Acadia Ladies Seminary was modelled after the prestigious Mt. Holyoake Seminary of South Hadley, Massachusetts, founded by Mary Lyon in 1837 as a pioneer institution of higher learning for women which included scientific curricula. One of their students, Caroline Wentworth, came from Mt. Holyoake and set up her own Seminary in Clarence, where Susie’s parents were so active in the religious and community life of Paradise.

Mount Holyoake Seminary

It would be interesting to know how Caroline came from New Hampshire to Clarence. When she married Edward Manning Morse of Paradise she re-established her Seminary in Paradise at their home in the outbuilding that still stands, educating both girls and boys. After her death, Edward, at age 58, married the widow of Israel Delap, a sea captain who died of yellow fever off the coast of West Africa. She was Lucretia Croscup, 48, and she and her daughter, Mary Amelia, came to Edward’s home in Paradise. So both of these young women had connections with Caroline Wentworth and the Seminary movement.

Alice Shaw, Annie Parker, and Rebecca Chase were three young Annapolis Valley Baptist women who went to Mt. Holyoake in 1854 and brought back their knowledge and support of its curriculum and institutional structure. Their enthusiasm was taken up by Rev. John Chase and led to the creation of a Seminary in Grand Pré.

Caroline Wentworth Morse

When Alice Shaw’s Grand Pré Seminary closed in 1872 and women moved in 1879 to the Seminary on the Acadia University campus, they were “pushing at the very doors of the university”.

President Artemus Sawyer’s reluctance (“You must not consider yourselves as members of the College, young ladies.”) could not stem the tide, as Margaret Conrad has pointed out in Women At Acadia University: The First Fifty Years: 1884-1934.

From the April 1899 edition of the Acadia Anthenaeum

The beautiful halls of Acadia Seminary building.

In 1884, Clara Belle Marshall was the first woman to be awarded a bachelor’s degree at Acadia—just nine years after Grace Annie Lockhart of Mount Allison had become the first woman to achieve a Canadian degree. Mary Lyon was proved right in the end. Providing academic quality for women would pave the way for their entry into university and a world beyond its doors.

And so the world was changed. Mary and Susie were part of it all.

Written by Barbara Bishop